2 Pulling remote changes

Now a new directory should have been created with the content of the repository in your local file system. From now on we will see the basic git commands that you would need in daily usage. We assume you are inside the repository. We explain them with an example.

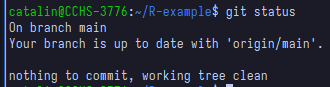

Suppose you want to start contributing to this repository. A good practice (and one that we will enforce to use) is to make your own code changes in a ‘different place’ than the ones you currently see in the repository. The things you see now are in what it is called the ‘main branch’, and you will make your code changes in a ‘new branch’, which will start with the same content as the main one, but will then evolve with different changes. If you have not done anything yet, you should be in the main branch (maybe it is called ‘main’ or ‘master’, these are just conventions, but I will assume it is called ‘main’). You can use the command git status to check this (do not mind that my terminal looks different in the screenshots, you can use the same commands in Git Bash):

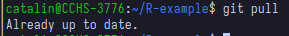

Your local version of a repository does not need to match the remote version (the one we store in GitHub in this case), but before you start your work on a new branch, you should keep your main branch up to date in case someone added new code in the GitHub repository since the last time you checked. We get any new remote changes to the local repository by using the command

git pull

In this case I already had all the remote changes, and that is why the message says ‘Already up to date’, but the message will be different if you had missing changes. This is the ‘easy way’ to do it. The command git pull tries to fetch changes from the equivalent remote branch, i.e., the one that has the same name on remote as it has on your local repository. This may not always work as expected so there is a way to always specify from which remote branch you want to get these changes (and I highly recommend always using it explicitly):

git pull origin <name-of-remote-branch>For example, imagine you asked someone for help on your own branch and they added some new changes on your branch, that you do not have locally. Then, if your branch is called my-branch, and you are already on your branch locally, you would want to use the command

git pull origin my-branchLikewise, for the first example shown here (keeping the main branch updated), I would always be explicit:

git pull origin main